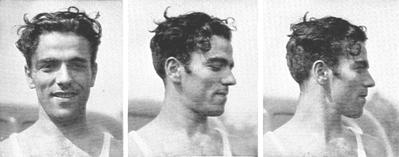

«The Coarse Mediterranean is the first type of Mediterranean that entered Europe going back to the

Mesolithic and earlier, its the Basic White of Lawrence Angel and the Europoid Archaic of Biasutti, the Southern Cromagnon of Lundman aka

Berid.»

Os Berid são claramente uma das populações pré-históricas de caçadores recoletores da Peninsula Ibérica.

Sobre o conceito de raça e ecótipo:

«On the Concept of Biological Race and Its Applicability to Humans

Massimo Pigliucci and Jonathan Kaplan

http://people.oregonstate.edu/~kaplanj/2003-PhilSc-race.pdf

"Biological research on race has often been seen as motivated by or lending credence to underlying racist attitudes; in part for this reason, recently philosophers and biologists have gone through great pains to essentially deny the existence of biological human races. We argue that human races, in the biological sense of local populations adapted to particular environments, do in fact exist; such races are best understood through the common ecological concept of ecotypes. However, human ecotypic races do not in general correspond with ‘folk’ racial categories, largely because many similar ecotypes have multiple independent origins. Consequently, while human natural races exist, they have little or nothing in common with ‘folk’ races."

"Races, then, can be defined and picked out in a number of ways. Several ways of picking out races will likely overlap because of the nature of biological organisms; for example, if a population is ecologically distinct (e.g., it lives at high elevations) it is also likely to be geographically isolated (by virtue of occurring in a location at high elevation) and to be somewhat genetically differentiated. But while genetic and phenotypic differences between local populations will often be associated with phylogenetic distinctiveness, such differences do not imply phylogenetic distinctiveness, nor, a fortiori, do they imply incipient speciation. For a lineage to acquire phylogenetic distinctiveness, gene flow with other closely related populations must essentially cease. If gene flow is still significant, the lineage is evolving according to a reticulate, not cladistic (branching) pattern. While it is still possible for such an entity to maintain

ecological distinctiveness (see below), its historical roots are continuously reshuffled by migration events. Thus, while ecogeographical-genetic differentiation tend to correlate with each other they do not imply cladogenesis and speciation, though the latter two are themselves associated.

That biologically meaningful races do not have to be phylogenetically distinct is obvious when we consider the case of ecotypes. The concept of ecotype was introduced by Turesson (1922) to describe genetically based specific responses of plants to certain environmental conditions, although the idea has been applied to the animal literature as well. The King and Stansfield’s dictionary defines an ecotype as a ‘‘Race (within a species) genetically adapted to a certain environment.’’ It is important to understand three things about ecotypes: (1) there must be a connection between genetic differentiation and ecological adaptation, (2) ecotypes are not (necessarily) phylogenetic units; rather, they are functional-ecological entities, and (3) ecotypes can be differentiated on the basis of many or a very few genetic differences.

These facts about ecotypes have several important implications. Similar ecotypic characteristics can and do evolve independently in geographically separated populations (see McPeek and Wellborn 1998). These similar phenotypic characteristics may, or may not, be mediated by similar genetic differences from other populations of the species (see Schlichting and Pigliucci 1998, 142–146, and cites therein). Further, gene flow between different ecotypes is relatively common (see Futuyma 1998, and cites therein); if there is sufficient selective pressure to maintain the genetic differences associated with the different adaptive phenotypes, other genes, not so associated, may flow freely between the populations. Further, because different ecologically important characteristics are not guaranteed to coincide, a single population can consist of multiple overlapping ecotypes. In such cases, whether two organisms belong to the same ecotype will depend on which ecotype one is referring to."

"Rather, human evolution seems to have been marked by extensive gene flow. While this implies that there are not now, nor ever were, biologically significant human races that corresponded to populations that had been phylogenetically separate for some significant period of time (contra Andreasen 1998), it does not imply, as some authors have argued, that there can be no significant biological races in humans. As we saw above in the case of ecotypes, adaptive genetic differentiation can be maintained between populations by natural selection even where there is significant gene flow between the populations. Templeton (1999), for example, notes that gene flow sufficient to ensure that distinct populations evolve together as a single species is compatible with the populations having distinct, genetically mediated, phenotypic adaptations. For example, he notes that there are populations of Drosophila mercatorum in Hawaii that ‘‘show extreme differentiation and local adaptation’’ yet have significant gene flow between them.

Lewontin and Gould have made much of the fact that there is relatively little genetic variation in Homo sapiens (compared at least to other mammals; see Templeton 1999) and that most of what genetic diversity is known to exist within Homo sapiens exists within (rather than between) local populations (see, for example, Gould 1996; Lewontin et al. 1984), and these facts are cited repeatedly in arguments concluding that there are no biologically significant human races. But the idea that this data might imply something about the existence of biologically significant human races emerges from a focus on the wrong sort of biological races. The relative lack of genetic variation between populations compared with within population samples does imply that the populations have not been reproductively isolated for any evolutionarily significant length of time. But of course, this fact is irrelevant for the consideration of races based on adaptive variation; in this case, if there is extensive gene flow, genetic variation can be mostly within groups, rather than between groups, as variations not related to the adaptive phenotypic differences between the populations will be spread by gene flow relatively easily. The question is not whether there are significant levels of between-population genetic variation overall, but whether there is variation in genes associated with significant adaptive differences between populations (see our discussion in Kaplan and Pigliucci 2001).

So, if we conceive of races similarly to the way ecotypes are conceived of, it is clear that much of the evidence used to suggest that there are no biologically significant human races is, in fact, irrelevant. As long as differences between populations can be maintained because of their adaptive significance, races can exist despite extensive gene flow between populations. The questions, then, are as follows: Do such conditions exist in the human case? and: Did such conditions exist during the course of human evolution such that the resultant differences might still be detectable today (though perhaps no longer actively maintained)?"

"Given the difficulty with testing hypotheses regarding the adaptive significance of behavioral tendencies in humans simpliciter (Lewontin 1998), the lack of evidence for behavioral (and/or intellectual) ecotypes in humans is not surprising. But it is intellectually dishonest to move from the lack of evidence for such differences to claiming that there is evidence for an absence of such differences, a move all too often made (oddly enough, both by Gould and by some of his opponents in ‘‘evolutionary psychology’’ (see, for example, Gould 1996, Tooby and Cosmides 1990))."

"A cline is a pattern of gradual variation of one or more characters, usually—but not exclusively—along a latitudinal or altitudinal range. Again, gene flow can be extensive through clines, as long as selective pressures are sufficient to maintain the genetic differences associated with adaptations to the ecologically important conditions (e.g., Jordan et al. 2001, Futuyma 1998). Given the wide geographical distribution of human populations over evolutionarily significant periods of time (Templeton 1999), it would be surprising if human populations did not show any clinal variation in ecologically important characteristics. The key points made above regarding ecotypes—that they may or may not be phylogenetic units and may or may not limit gene flow—also hold true for clinal variations, as does the observation that an individual may simultaneously be a member of multiple different ecotypes (as in multiclinal variation).

Of course, this implies that insofar as we focus on an ecotype conception of race, there will not necessarily be a unique ‘‘race’’ to which any given member of a population belongs. Any given individual may in fact belong to a number of different ecotypic races, and/or be a member of one (or more) intermediate population(s) within a (series of) clinal distribution(s). However, this is hardly an unexpected complication in a discipline like biology, characterized by a high level of complexity of both the object of study and the conditions that induce variation in that object.

The problem posed by clines, then, is no different from that posed by any other gradual transition, and provides no reason to reject the possibility of the existence of biologically significant human races."

"As we have seen, insofar as biologically meaningful races are conceptualized as populations more like ecotypes than like incipient species, many of the arguments purporting to show that there are no human races miss their mark. While in nonhuman biology the term ‘‘race’’ has been and is being used in a variety of ways, the best way of making sense of systematic variation within the human species is likely to rely on the ecotypic conception of biological races. In this sense, there are likely human races (ecotypes) of biological interest."

"While it is valuable for biologists to note that the essentialist conception of human races has no support in biology whenever particular claims are made that seem predicated on such a conception (e.g., Herrnstein and Murray’s 1994 work on race and intelligence), they should not fall into the trap of claiming that there is no systematic variation within human populations of interest to biology."